Kalu Rinpoche's New Dharma Rock Music - " We need you "

|

우리는 당신이 필요해요 : : WE NEED YOU

| Hoh~ ohoh~ people in this world

Suffer so much, suffer too much

호~ 오오~ 이 세계의 사람들은

너무나 많은 고통을 겪고 있어요.

너무나 많은 고통을 겪고 있어요.

I’d hard to know.

It’s hard to know what to do

It’s hard to know what to do

난 너무나 알기 어려웠죠.

무엇을 해야 할지 너무나 알기 어려웠어요.

무얼 해야 할지 너무나 알기 어려웠어요.

Life is too short, life is too short

It is so precious but yet is too short

삶은 너무나 짧아요, 삶은 너무나 짧아요.

너무나 소중하지만- 그러나 너무나 짧아요.

People suffer from disease

People suffer from hunger

People suffer from disaster

Earthquakes and Tsunami

질병으로 고통받는 사람들

배고픔으로 고통받는 사람들

재난으로 고통받는 사람들

지진과 쓰나미로 고통받고 있는…

We’ve suffered so much

We’ve suffered so much

Please bodhisattvas bless us

우리는 너무나 많이 고통받아 왔어요.

우리는 너무나 많이 고통받아 왔어요.

보살님들이시여 제발 우리를 축복해주세요.

We know you love us, we know you care

We need you to be with us now

Whether we are good or whether we are not

We all need you,

우리는 당신이 우리를 사랑하신다는 걸 알고 있어요.

우리는 당신이 우리를 돌보신다는 걸 알고 있어요.

우리가 좋은이 이든 나쁜이 이든 간에

우리 모두는 당신이 필요해요,

Please show us you care

Show us your love

We need your love

We need it now

제발 당신이 우리를 돌보신다는 것을 보여주세요.

당신의 사랑을 보여주세요.

우리는 당신의 사랑이 필요해요.

지금 당장 필요해요.

| Politicians play politics

Painful in our heart

Trying to get a job

Cannot get a job

정치인들은 정치를 가지고 놀고

우리의 가슴을 아프게 할 뿐이죠

직장을 구하려고 하지만

직장도 구할 수가 없어요

Depending on our family

Couldn’t understand us

Painful painful painful painful

우리네 가족들은 자신들의 생각만 따를 뿐

그들은 우리를 이해하지도 못했어요.

고통스러워요 고통스러워 고통스러워 고통스러워

We’ve suffered so much

We’ve suffered so much

Please bodhisattvas bless us

우리는 너무나 많이 고통받아 왔어요.

우리는 너무나 많이 고통받아 왔어요.

보살님들이시여 제발 우리를 축복해주세요.

We know you love us, we know you care

We need you to be with us now

Whether we are good or whether we are not

We all need you,

우리는 당신이 우리를 사랑하신다는 걸 알고 있어요.

우리는 당신이 우리를 돌보신다는 걸 알고 있어요.

우리가 좋은이 이든 나쁜이 이든 간에

우리 모두는 당신이 필요해요,

Please show us you care

Show us your love

We need your love

We need it now

제발 당신이 우리를 돌보신다는 것을 보여주세요.

당신의 사랑을 보여주세요.

우리는 당신의 사랑이 필요해요.

우리는 지금 필요해요.

We think that money will give us freedom

To do whatever we want

But this money’s just paper

Made to play the game

우리는 돈이 우리에게 자유를 줄 거라고 생각하죠.

우리가 무엇을 원하든 할 수 있게 해줄 거라고.

그러나 이 돈은 그저 종이일 뿐이에요.

당신을 이 시스템에 묶어두기 위한!

We’ve suffered so much

We’ve suffered so much

Please bodhisattvas bless us

우리는 너무나 많이 고통받아 왔어요.

우리는 너무나 많이 고통받아 왔어요.

보살님들이시여 제발 우리를 축복해주세요.

We know you love us, we know you care

We need you to be with us now

Whether we are good or whether we are not

We all need you,

우리는 당신이 우리를 사랑하신다는 것을 알고 있어요.

우리는 당신이 우리를 돌보신다는 것을 알고 있어요.

우리가 좋은 이 이던지 나쁜 이 이던지 간에

우리 모두는 당신이 필요해요,

Please show us you care

Show us your love

We need your love

We need it now

제발 당신이 우리를 돌보신다는 것을 보여주세요.

당신의 사랑을 보여주세요.

우리는 당신의 사랑이 필요해요.

지금 당장 필요해요.

Dharma politics Dharma business

I don’t want to fall into this trap

I call to the bodhisattvas

I believe in pure dharma

불법이라는 이름의 정치, 불법의 이름을 빌린 장사

저는 이 덫 속에 빠져들고 싶지 않아요.

제가 보살님들께 요청 드리고 있어요.

저는 순수한 다르마를 믿고 있어요.

We’ve suffered so much

We’ve suffered so much

Please bodhisattvas bless us

우리는 너무나 많이 고통받아 왔어요.

우리는 너무나 많이 고통받아 왔어요.

보살님들이시여 제발 우리를 축복해주세요.

We know you love us, we know you care

We need you to be with us now

Whether we are good or whether we are not

We all need you,

우리는 당신이 우리를 사랑하신다는 것을 알고 있어요.

우리는 당신이 우리를 돌보신다는 것을 알고 있어요.

우리가 좋은 이 이던지 나쁜 이 이던지 간에

우리 모두는 당신이 필요해요,

Please show us you care

Show us your love

We need your love

We need it now

제발 당신이 우리를 돌보신다는 것을 보여주세요.

당신의 사랑을 보여주세요.

우리는 당신의 사랑이 필요해요.

우리는 지금 필요해요.

Whatever we believe in,

Our deepest wish

Is to bring happiness

Happiness to all

우리가 무엇을 믿든지 간에

우리의 가장 깊은 소원은

행복을 가져오는 것

모두에게 행복을 가져다 주는 것

| Let love cover the world, love without attachment !!!

Let love cover the world, love without attachment !!!

사랑으로 이 세계를 덮어 나가요. 집착 없는 이 사랑으로 !!!

사랑으로 이 세계를 덮어 나가요. 집착 없는 이 사랑으로 !!!

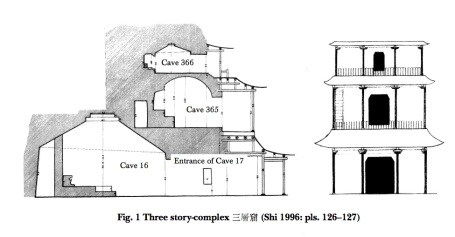

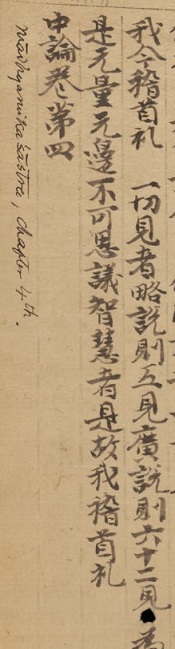

As he promised in his vow, Daozhen collected unwanted fragmentary or duplicate manuscripts, and used them to fill gaps in the Sanjie monastery’s library, or to repair incomplete works in that library. Thus according to Rong, the existence of so many incomplete manuscripts in the Dunhuang cave is due to Daozhen’s efforts in collecting manuscripts from elsewhere. Rong also pointed out that many of the manuscripts are not actually incomplete, and seem to have been originally stored in the cave in neatly catalogued bundles.

As he promised in his vow, Daozhen collected unwanted fragmentary or duplicate manuscripts, and used them to fill gaps in the Sanjie monastery’s library, or to repair incomplete works in that library. Thus according to Rong, the existence of so many incomplete manuscripts in the Dunhuang cave is due to Daozhen’s efforts in collecting manuscripts from elsewhere. Rong also pointed out that many of the manuscripts are not actually incomplete, and seem to have been originally stored in the cave in neatly catalogued bundles.